Readings: FileIO & Exceptions

Reading and Writing Files in Python (Guide)

What Is a File?

Files on most modern file systems are composed of three main parts:

- Header: metadata about the contents of the file (file name, size, type, and so on)

- Data: contents of the file as written by the creator or editor

- End of file (EOF): special character that indicates the end of the file

- What this data represents depends on the format specification used, which is typically represented by an extension.

File Paths

When you access a file on an operating system, a file path is required. The file path is a string that represents the location of a file. It’s broken up into three major parts:

- Folder Path: the file folder location on the file system where subsequent folders are separated by a forward slash / (Unix) or backslash \ (Windows)

- File Name: the actual name of the file

- Extension: the end of the file path pre-pended with a period (.) used to indicate the file type

Opening and Closing a File in Python

When you want to work with a file, the first thing to do is to open it. This is done by invoking the open() built-in function. open() has a single required argument that is the path to the file. open() has a single return, the file object:

file = open('dog_breeds.txt')

Warning: You should always make sure that an open file is properly closed. When you’re manipulating a file, there are two ways that you can use to ensure that a file is closed properly, even when encountering an error. The first way to close a file is to use the try-finally block:

reader = open('dog_breeds.txt')

try:

# Further file processing goes here

finally:

reader.close()

The second way to close a file is to use the with statement:

with open('dog_breeds.txt') as reader:

# Further file processing goes here

The with statement automatically takes care of closing the file once it leaves the with block, even in cases of error.

the most commonly used options for modes are the following: |Character|Meaning| |–|–| |’r’| Open for reading (default)| |’w’| Open for writing, truncating (overwriting) the file first| |’rb’ or ‘wb’| Open in binary mode (read/write using byte data)|

open('abc.txt')

open('abc.txt', 'r')

open('abc.txt', 'w')

Reading and Writing Opened Files

Once you’ve opened up a file, you’ll want to read or write to the file. First off, let’s cover reading a file. There are multiple methods that can be called on a file object to help you out: |Method |What It Does| |–|–| |.read(size=-1) |This reads from the file based on the number of size bytes. If no argument is passed or None or -1 is passed, then the entire file is read.| |.readline(size=-1) |This reads at most size number of characters from the line. This continues to the end of the line and then wraps back around. If no argument is passed or None or -1 is passed, then the entire line (or rest of the line) is read.| |.readlines() |This reads the remaining lines from the file object and returns them as a list.|

Now let’s dive into writing files. As with reading files, file objects have multiple methods that are useful for writing to a file:

| Method | What It Does |

|---|---|

| .write(string) | This writes the string to the file. |

| .writelines(seq) | This writes the sequence to the file. No line endings are appended to each sequence item. It’s up to you to add the appropriate line ending(s). |

Tips and Tricks

Now that you’ve mastered the basics of reading and writing files, here are some tips and tricks to help you grow your skills.

__file__

The __file__ attribute is a special attribute of modules, similar to __name__. It is:

“the pathname of the file from which the module was loaded, if it was loaded from a file.”

Appending to a File

Sometimes, you may want to append to a file or start writing at the end of an already populated file. This is easily done by using the ‘a’ character for the mode argument:

with open('dog_breeds.txt', 'a') as a_writer:

a_writer.write('\nBeagle')

Working With Two Files at the Same Time

There are times when you may want to read a file and write to another file at the same time. If you use the example that was shown when you were learning how to write to a file, it can actually be combined into the following:

d_path = 'dog_breeds.txt'

d_r_path = 'dog_breeds_reversed.txt'

with open(d_path, 'r') as reader, open(d_r_path, 'w') as writer:

dog_breeds = reader.readlines()

writer.writelines(reversed(dog_breeds))

Python Exceptions: An Introduction

Exceptions versus Syntax Errors

Syntax errors occur when the parser detects an incorrect statement.

>>> print( 0 / 0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zero

This time, you ran into an exception error. This type of error occurs whenever syntactically correct Python code results in an error. The last line of the message indicated what type of exception error you ran into.

Raising an Exception

We can use raise to throw an exception if a condition occurs. The statement can be complemented with a custom exception.

If you want to throw an error when a certain condition occurs using raise, you could go about it like this:

x = 10

if x > 5:

raise Exception('x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: {}'.format(x))

When you run this code, the output will be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 4, in <module>

Exception: x should not exceed 5. The value of x was: 10

The program comes to a halt and displays our exception to screen, offering clues about what went wrong.

The AssertionError Exception

Instead of waiting for a program to crash midway, you can also start by making an assertion in Python. We assert that a certain condition is met. If this condition turns out to be True, then that is excellent! The program can continue. If the condition turns out to be False, you can have t

Have a look at the following example, where it is asserted that the code will be executed on a Linux system:

import sys

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "This code runs on Linux only."

If you run this code on a Linux machine, the assertion passes. If you were to run this code on a Windows machine, the outcome of the assertion would be False and the result would be the following:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 2, in <module>

AssertionError: This code runs on Linux only.

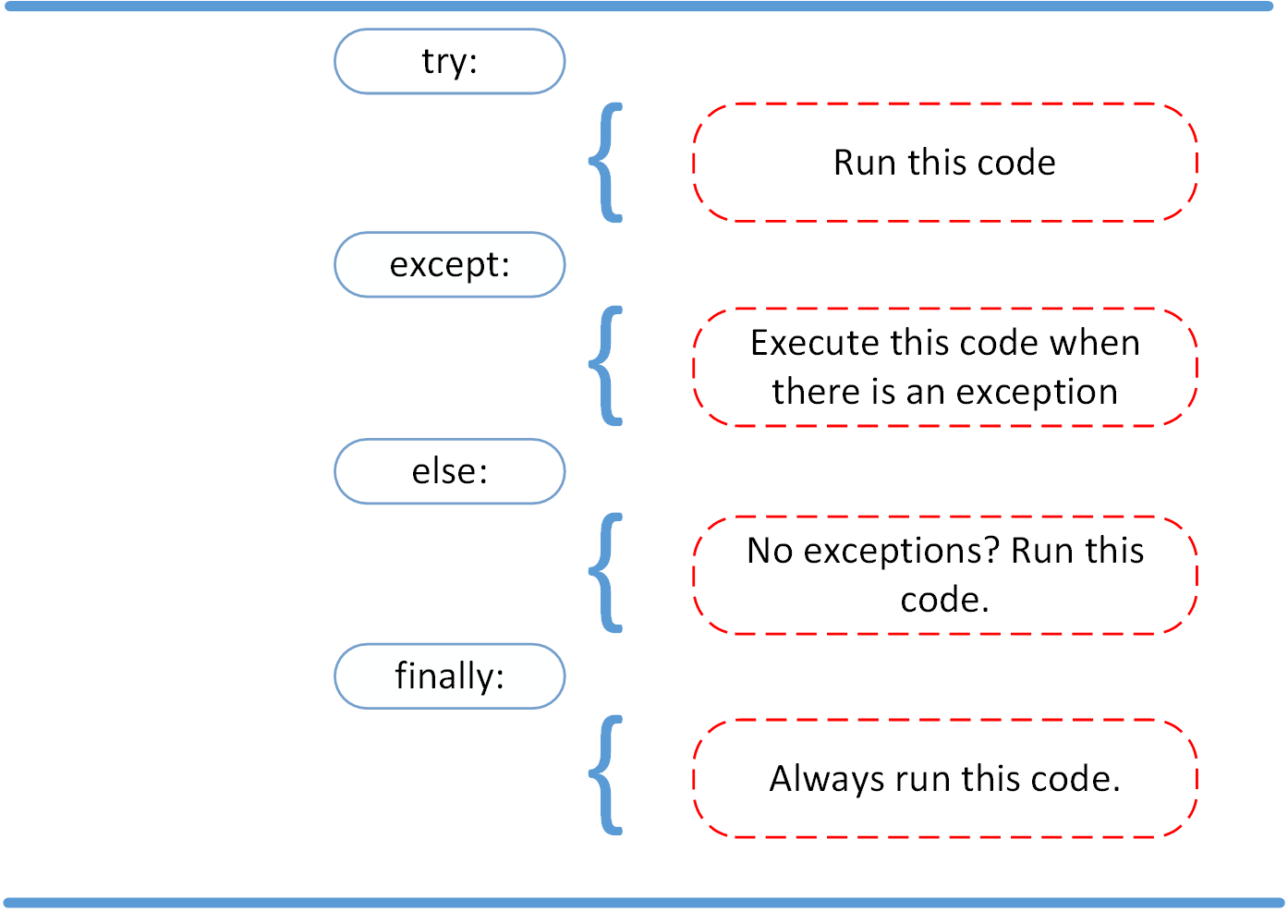

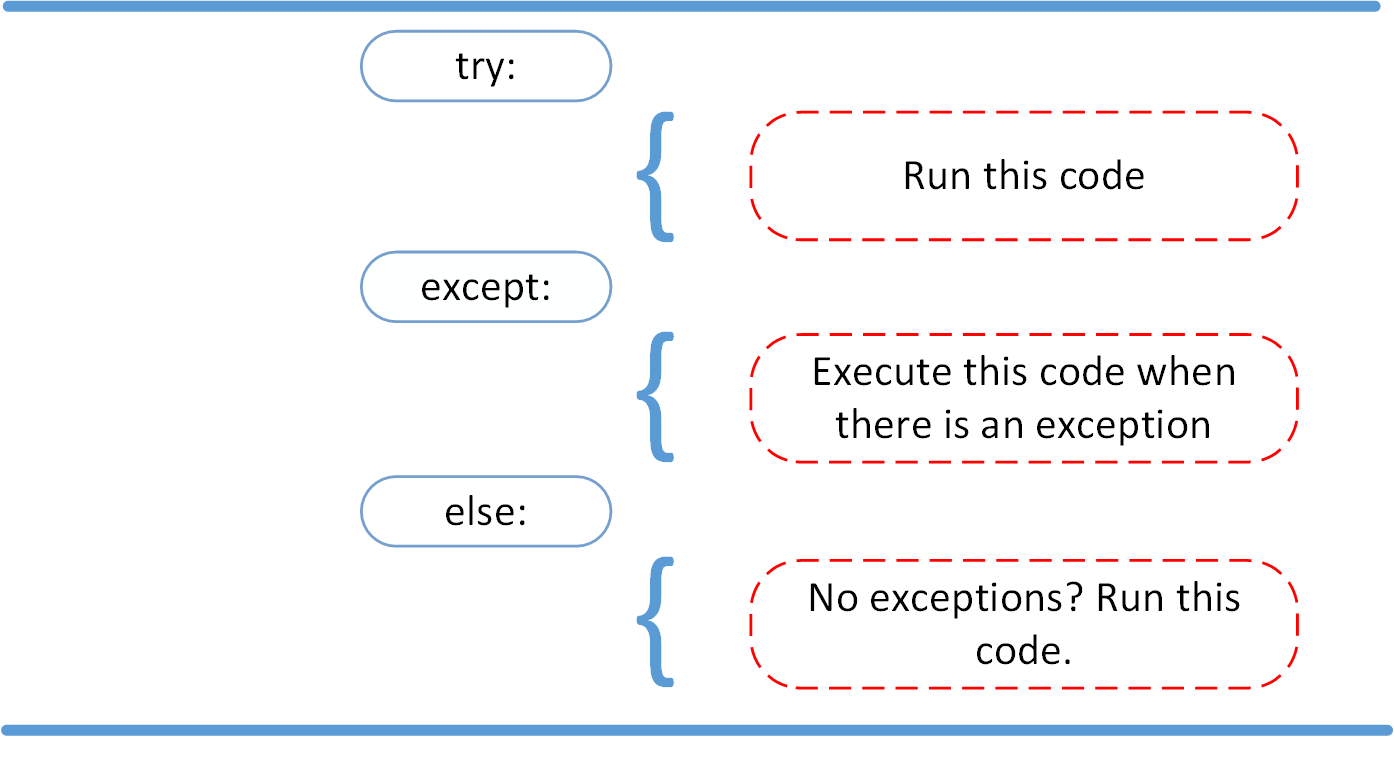

The try and except Block: Handling Exceptions

The try and except block in Python is used to catch and handle exceptions. Python executes code following the try statement as a “normal” part of the program. The code that follows the except statement is the program’s response to any exceptions in the preceding try clause.

As you saw earlier, when syntactically correct code runs into an error, Python will throw an exception error. This exception error will crash the program if it is unhandled. The except clause determines how your program responds to exceptions.

def linux_interaction():

assert ('linux' in sys.platform), "Function can only run on Linux systems."

print('Doing something.')

try:

linux_interaction()

except:

print('Linux function was not executed')

so the Linux function will not be run

When an exception occurs in a program running this function, the program will continue as well as inform you about the fact that the function call was not successful.

What you did not get to see was the type of error that was thrown as a result of the function call. In order to see exactly what went wrong, you would need to catch the error that the function threw.

The following code is an example where you capture the AssertionError and output that message to screen:

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

print('The linux_interaction() function was not executed')

The else Clause

In Python, using the else statement, you can instruct a program to execute a certain block of code only in the absence of exceptions.

try:

linux_interaction()

except AssertionError as error:

print(error)

else:

print('Executing the else clause.')

If you were to run this code on a Linux system, the output would be the following:

Doing something.

Executing the else clause.

Because the program did not run into any exceptions, the else clause was executed.

Cleaning Up After Using finally

Imagine that you always had to implement some sort of action to clean up after executing your code. Python enables you to do so using the finally clause.